When you think of Tarot cards, you probably envision a woman with a cloth around her head laying out upon a table a series of cards with illustrations on them to divine the future. This is the image propagated by Hollywood. While there may be some fortune tellers who dress this way because that is what expected by a paying client, most tarot readers are just like you. They own a deck and do self readings and readings for friends and family using cards like The Fool, The Magician, Death, The Devil, The Hermit, The Tower or any other of the severity-eight cards contained in a Tarot deck.

The Rider Waite deck is the most recognizable deck in the world today. The Rider Waite deck helped make Tarot a recognizable instrument of divination for persons who are not familiar with the mystical arts. The Rider Deck created by Waite, in particular, has become the most recognizable deck in the world today for a special kind of divination called cartomancy. Cartomancy is the use of cards for fortune telling. As esotericist A.E. Waite wrote, the Tarot is what appears to be “simply a well-known method of fortune-telling.”

But it is much, much more.

Early history and origins of the Tarot deck

Both Dr. Arthur Edmund Waite and Aleister Crowley mention of scholars that try to place the Tarot deck as far back as ancient Egypt. Court de Gebelin wrote in “La Monde Primitif” proclaimed in 1781 that the Tarot deck was created based upon the Egyptian work, The Book of Thoth. Thoth, according to Egyptian mythology, was the creator of the hieroglyphic system and these images eventually made it onto cards and were dispersed by Romani throughout Europe. There are no extant examples of cards in this ancient tradition so ancient Egyptian decks are circumspect at best.

We know that the Tarot deck was being used in the mid-14th century. In 1332, King Alfonse XI of Leon and Castile issued a decree prohibiting the use of Tarot cards. The Roman Catholic Church also condemned the cards and prohibited their use by labeling them as “The Devil’s Bible” and “The Devil’s Picture Book.” In Germany, a monk named Johannes wrote of a game in 1377 called Ludas Cartarum that used these same cards. He described these cards as being a mirror of society as the represented “…the state of the world as we now know most excellently described and figured.” Outside of religious structures, the name “Tarot of the Bohemians” was also used in the Middle Ages to describe the cards.

The earliest cards known to still exist are in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. There are seventeen hand-painted cards that are believed to have been painted by Jacquemin Gringonneur in 1392 for Charles VI of France; but there is evidence that these cards may be later and of mid-15th century Venetian design.

What all Tarot scholars agree upon is the creation of the modern deck occurred in the early to late fifteenth century by an Italian artist named Bonifacio Bembo. The cards that Bembo painted were unnamed and unnumbered for the Visconti family, a prominent noble family in Milan. Today, that deck is known as the Visconti-Sforza Tarot Deck.

Bembo initially painted twenty-two cards which became the basis of an Italian game called Tarocchi. This game had four distinct suits of fourteen cards, plus twenty-two cards called depicting various scenes. The twenty two cards were named Trionfi, which in English translates to trumps or triumphs.

T-Shirts, Mugs and More!

We now have t-shirts, tarot decks, ESP cards, coffee mugs, face masks, and much more merchandise available for purchase. Every dollar spent helps fund Paranormal Study!

There are thirty-five of Bembo’s card designs located in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York City that were believed to have been painted circa 1484; scholars are unsure whether these were painted by Bembo or his contemporary, Antonio Cicognara. These particular cards belonged to Cardinal Ascanio Maria Sforza and were likely used as pictorial representations of the era.

There are several other decks of historical cards that were used in Europe that ranged from the traditional seventy-eight card deck to variant decks of fifty, sixty-two and other numbers. Over time, the seventy-eight card deck won and has become the standard number of cards used for tarot in modern times.

It is important to note that before the Reformation, most people in Europe were not literate; there was not widespread literacy as a norm until the early twentieth century. In fact, pre-Reformation, literacy was condemned by religious institutions to prevent individual interpretations of religious works. This changed with the invention of the Gutenberg Press in 1436, but only nobles and clergy had access to written text for an extended period of time after the invention of the press.

There are esotericists who believe that the Major Arcana (Trumps) were painted as an ars memorativa, a pictorial memory system, of occult teachings for students of the occult during the Renaissance. The images are archetypal images that stand the test of time and had an allure for those who had no access to books. So despite the decree of the Church, Tarot spread throughout Europe and soon became used in the art of fortune telling.

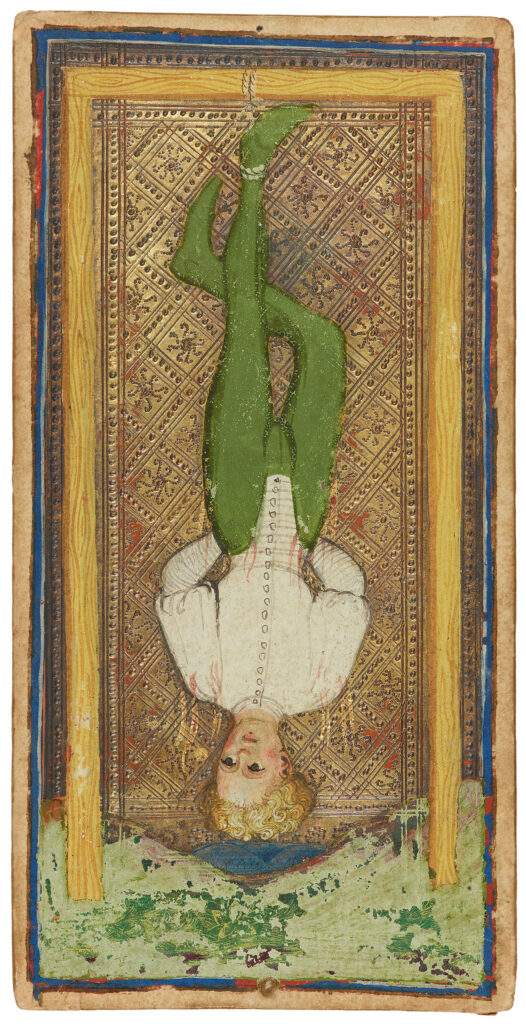

An example of ars memorativa

A great example of this form of handing down occult knowledge to initiates through images can be found in The Hanged Man.

The Hanged Man is a specific Tarot card that has continued in use since the first cards painted by Bembo. At first, this card may appear to the casual observer that this man is in a horrific predicament as he hangs upside down from a wooden frame. You’ll note that his right leg is positioned behind his leg forming both a cross and the number four. His hands form a triangle behind his back. His face is peaceful and his head is illuminated in the Waite deck, but contains a shock of radiant hair in the historical Bembo deck.

Through examining Bembo’s representations of The Hanged Man, Rachel Pollack in her very influential work Seventy Eight Degrees of Wisdom wrote about historical representations of being hung upside down in ancient religious traditions. Moreover, she points to this card, and every card in the deck, potentially representing an esoteric tradition:

Where did Bembo derive this image? It certainly does not represent a criminal hanged at the gallows, as some later artists have assumed. In Italy, modern Italian decks call this card L’Apezzo, the Traitor. But there is no evil implicit in Bembo’s figure. The young man appears beautiful, and at peace.

Christian tradition describes St. Peter as being crucified upside down, ostensibly so he could not be said to be copying his Lord. The Elder Edda describes the god Odin hanging from the World Tree for nine days and nights, not as a punishment, but in order to receive enlightenment, the gift of prophecy. But this mythological scene itself derives from he actual practice of shamans, medicine men, in such places as Siberia and North America. In the initiation and training the candidates for shamanism are sometimes told to hang upside down. Apparently the reversal of the body produces some sort of psychological benefit, in the way that starvation and extreme cold will induce radiant visions. The alchemists – who, with the witch, were possibly the survivors of the shamanist tradition in Europe – also hung themselves upside down, believing that the elements in the sperm vital to immortality would thus flow down to the psychic centers at the top of the head. And even before the West began to take Yoga seriously everyone knew the image of the yogi standing on his head.

Did Bembo simply wish to represent an alchemist? Then why no use the more common image, that of a bearded man stirring a cauldron or mixing chemicals? The picture, titled “The Hanged Man” in subsequent decks and later made famous by T.S. Eliot in The Wasteland, appears not so much as an alchemist as a young initiate in some secret tradition. Was Bembo himself an initiate? The special crossing of the legs would suggest so. And if he included one reference to esoteric practices, might not the other images, superficially a social commentary, in reality represent an entire body of occult knowledge?

Pollack, “Seventy Eight Degrees of Wisdom,” pages 3-4

As we will discuss in the next article, there are numerous esoteric scholars who help to interpret the meaning on the Tarot cards. The Rider Waite deck, for example, was created under the direction of AE Waite who was a renowned esoteric scholar. Though the work of Crowley, Waite, and Levi, we will examine the esoteric leanings of the Tarot cards to prepare you for the esoteric interpretations of the cards themselves.

If you found the content in this article to be of any value to your paranormal studies, please let us know in the comments below. Feel free to share this article with your friends as well because if you found it interesting, they might too.

Do You Want To Know More?

Our content creators also have podcasts that go much deeper into paranormal topics.

Tim Woolworth’s Walk in the Shadows, an episodic masterclass that consists of a deep dive into all things Fortean, paranormal and supernatural.

Rick Hale teams up with Stephen Lancaster in The Shadow Initiative where they explore various paranormal topics and discuss current paranormal news.

Please check these shows out and visit Paranormal Study social media to keep up to date on articles and all the things our authors are doing.

Be the first to comment